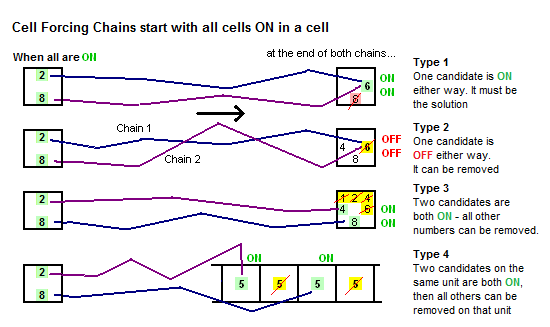

Cell Forcing Chains

Forcing Chains are a powerful extension of chain strategies. Given that a cell or unit contains certain numbers, and that these are the only alternatives, we can show that certain candidates must be eliminated. Specifically we show that *all* of the alternatives must eliminate the target. The chains force the removal as no alternative exists.

Dual Cell Forcing Chains

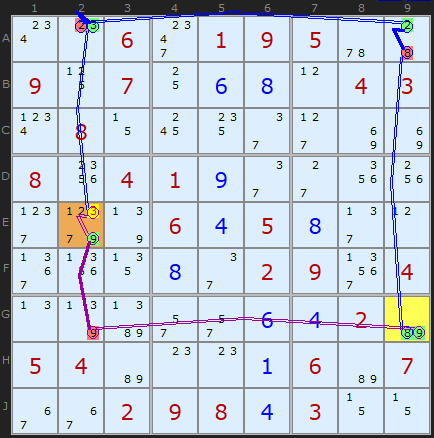

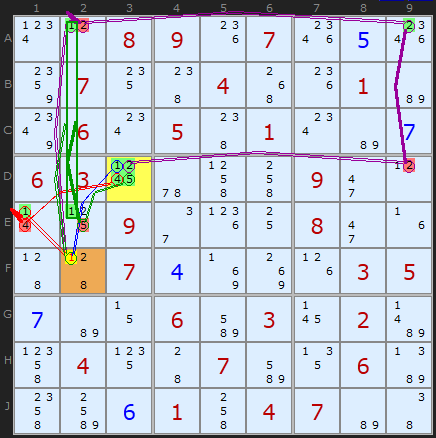

In the first example, we can eliminate 3 in E2 because of the numbers left in G9, the 8 and 9 there. The small purple chain shows that with two 9s in row G and column 2 a 9 in G9 places a 9 in in E2 and therefore removes the 3. The chain is +9[G9]-9[G2]+9[E2]-3[E2].

The 8 in G9 takes a little longer but again it is just a matter of following pairs in units. We remove the 8 in A9 giving 2 which forces a 3 in A2 and that removes the 3 in E2.

Since we are arguing from a single cell and the cell has two candidates, this is the simplest Forcing Chain, a Dual Cell Forcing Chain.

Note: Dual Cell Forcing Chains are not found by the solver because the solver will find Digit Forcing Chains first. The reason is that one of the two candidates that would make a Duel Cell Forcing Chain would be part of the chain on the Digit Forcing Chain. In this example perhaps the 2 in A2 would be considered first. Then -2[A2] would imply +3[A2] and the chain continues with the same consequences. Dual Cell Forcing Chains are documented here as an alternative approach as as part of a family sequence. The example above can be artifically induced by unticking AIC and DFC in the solver.

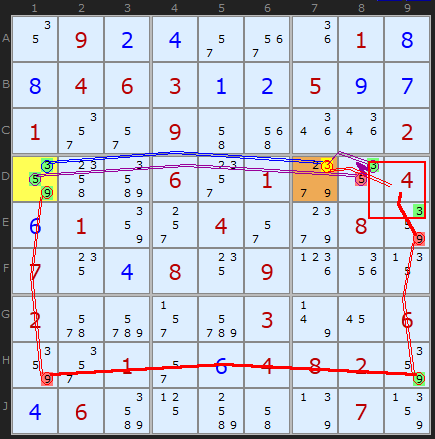

Triple Cell Forcing Chains

The second chain +5[D1]-5[D8]+3[D8]-3[D7] is a little more involved. The 5 in D1 must remove the 3 in D7. 5 will force a 3 in D8 which does the trick.

Now to force 9 in D1 to remove the 3 in D7 we have to use quite a complex chain. It reads +9[D1]-9[H1]+9[H9]-9[E9]

+3{E9|D8}-3[D7]. The curly brackets is my symbol for an ALS (Almost Locked Set). Documentation forthcoming.

In red, the chain starts with a 9 in D1 (+9). Removing the 9 in H1 means the 9 must be in H9 as its the last in the row. If that is the case we must remove the 9 from E9. E9 is interesting as it forms part of an Almost Locked Set with D8. An ALS is a set of N cells with N+1 candidates. In this case {3,5,9}. But by removing the 9 from E9 we have reduced and Almost Locked Set to a Locked Set. A 2-cell locked set is a Naked Pair. 3 and 5 must exist in D8 and E9 - we just don't know which way round yet. If this is the case then 3 can't exist in D7.

Viola, we have forced 3 from D7 using the contents of D1.

Viola, we have forced 3 from D7 using the contents of D1.

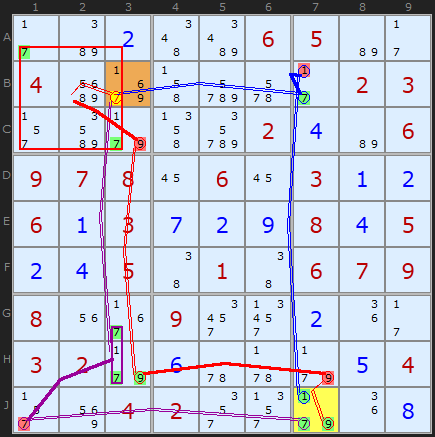

The purple chain, +7[J7]-7[J1]+7[G3|H3]-7[B3] contains an interesting group, symbolised by +7[G3|H3]. All this means is that if J1 is not a 7 then G3 OR H3 must be. If one of those must be 7 we can look along their alignment - the columns, and remove 7s, eg 7 in B3.

The last chain, +9[J7]-9[H7]+9[H3]

-9[C3]+7{C3|A1}-7[B3] contains an ALS, which I described above. We have a {1,7,9} in two cells A1 and C3. Removing 9 from B3 leaves a locked set of 1/7 in that box. All other 1s and 7s can be removed, namely the 7 in B3.

Quad Cell Forcing Chains

Logic relentlessly obliges us to consider the Quad formation, although I have not and will not look for higher order forcing chains, although they are possible. Quads are pretty rare. I found 6 in a random stock of forty thousand puzzles.

If there is a 1 in D3 it follows that

+1[D3]-1[F2]

If there is a 2 in D3 it follows that

+2[D3]-2[D9]+2[A9]-2[A2]+1[A2]-1[F2]

If there is a 4 in D3 it follows that

+4[D3]-4[E1]+1[E1]-1[F2]

If there is a 5 in D3 it follows that

+5[D3]-5[E2]+1{E2|A2}-1[F2].

Comments

Email addresses are never displayed, but they are required to confirm your comments. When you enter your name and email address, you'll be sent a link to confirm your comment. Line breaks and paragraphs are automatically converted - no need to use <p> or <br> tags.

... by: Glenn

... by: Anthony Louws

... by: rocannon

9's chain is not necessary. If D1<>9 than {D1, D8}=3/5.

Thanks your site! (from Korea)